Classic bikes: are they just for polishing, or should we use them in the way intended? If the classic is a road bike the question may not be too difficult, the occasional ride on a fine summer day can't do much harm. But what about riding an over sixty year old off roader like this 1952 Triumph TR5 Trophy, if the route were to include seriously challenging hills, deep ruts and glutinous mud?

I’m of the school that classic bikes should be ridden and if they are an off road model like this 1952 Triumph TR5 then at least occasionally they should be turned towards the off road challenges they were designed to take on. That said, I do appreciate that for many owning a classic bike in showroom condition is as compelling as my desire to put my bikes through their paces, however I liken it to restoring a classic aircraft and then confining yourself to taxing around the air strip. Don't you want to know how it flies?

COMPETITION MODEL

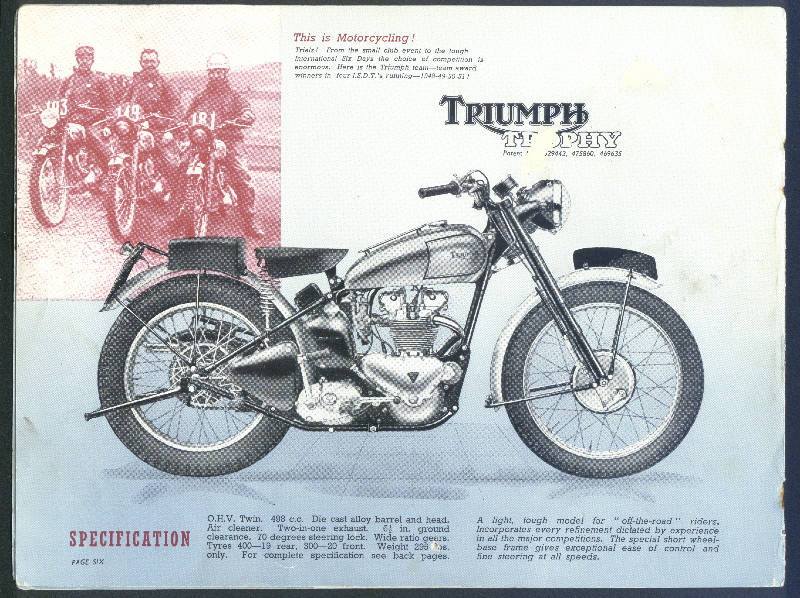

The rigid framed Triumph Trophy was a genuine competition bike, so named because in 1948 the Triumph factory team rode three of the then prototype models to Gold medal finishes in the International Six Days Trial (now called the International Six Days Enduro) thus winning a coveted manufacturers Trophy for the three man team. Triumph repeated the feat in three successive years, further justifying the Trophy name that graced Triumph’s off road oriented models during the 1950s and 1960s. Today Triumph tack this illustrious name to a road bike, but that’s another issue.

COMPETITION MODEL

The rigid framed Triumph Trophy was a genuine competition bike, so named because in 1948 the Triumph factory team rode three of the then prototype models to Gold medal finishes in the International Six Days Trial (now called the International Six Days Enduro) thus winning a coveted manufacturers Trophy for the three man team. Triumph repeated the feat in three successive years, further justifying the Trophy name that graced Triumph’s off road oriented models during the 1950s and 1960s. Today Triumph tack this illustrious name to a road bike, but that’s another issue.

Following the ISDT success in 1948, Triumph offered a replica of the rigid framed Trophy for limited sale to customers from 1949 to 1954. This bike was very different to the base 500cc road models and featured a lighter, shorter frame, smaller fuel tank, special adjustable seat and larger 20 inch front wheel. The engine was also modified with an alloy barrel and cylinder head in place of the cast iron units fitted to the road bikes and a wide ratio four-speed cluster in the non-unit transmission to cope with varied off road conditions.

Engine specification changed over time and optional tuning parts were also available so that TR5s are now seen in various states of tune. Earlier models with the wide pitch generator cylinder heads were generally tuned for greater low end power to double as trials mounts, while later examples with the fine pitch splayed port heads like this example were tending towards a more powerful enduro specification to suit increasing demand from enduro riders the USA. In all only 2475 rigid Trophys were built, making this a fairly rare Triumph model today.

Engine specification changed over time and optional tuning parts were also available so that TR5s are now seen in various states of tune. Earlier models with the wide pitch generator cylinder heads were generally tuned for greater low end power to double as trials mounts, while later examples with the fine pitch splayed port heads like this example were tending towards a more powerful enduro specification to suit increasing demand from enduro riders the USA. In all only 2475 rigid Trophys were built, making this a fairly rare Triumph model today.

RIDING A 62 YEAR OLD DIRT BIKE

To get an idea of what it is really like to ride a 62 year old dirt bike under tough off road conditions I enlisted the help of long time riding buddy Dene Humphrey to accompany me on an ambitious all-day crossing of the rugged Coromandel Ranges via the old Puriri to Hikuai pack horse track. Dene is a former NZ Enduro Champion and magazine test rider who also just happens to own his father's beloved BSA B50 MX, so he's no stranger to many of the idiosyncracies of riding classic British iron off road.

When the TR5 was built the modern tar sealed Highway 25A that now crosses the ranges was just a dream. To cross the peninsular road traffic then had to go north from Thames over the windy gravel Tapu Coroglen road, or many miles south via Paeroa and Waihi and many many more miles of tortuous gravel.

Our crossing would shun modern roads and follow the old gold miners packhorse trail. This climbs the Coromandel Ranges steeply in places past the site of the abandoned Neavesville gold mining and timber milling settlement and down the mountain to Puriri. The track nowadays is in very rough condition with ruts, bogs and mud holes that usually challenge riders on modern machinery. To make the crossing authentic we would ride from east to west, tackling steeper uphill grades.

When the TR5 was built the modern tar sealed Highway 25A that now crosses the ranges was just a dream. To cross the peninsular road traffic then had to go north from Thames over the windy gravel Tapu Coroglen road, or many miles south via Paeroa and Waihi and many many more miles of tortuous gravel.

Our crossing would shun modern roads and follow the old gold miners packhorse trail. This climbs the Coromandel Ranges steeply in places past the site of the abandoned Neavesville gold mining and timber milling settlement and down the mountain to Puriri. The track nowadays is in very rough condition with ruts, bogs and mud holes that usually challenge riders on modern machinery. To make the crossing authentic we would ride from east to west, tackling steeper uphill grades.

Partner bike for the ride was a unit T100C ISDT replica.

Partner bike for the ride was a unit T100C ISDT replica.

The partner bike for the journey was also something of an old timer, a unit construction 1968 500cc triumph T100C ISDE replica, a machine that echoes Triumph's later factory competition efforts. This bike is also fitted with wide ratio gearbox, but thankfully by this age graced with 4 luxurious inches of rear suspension.

Without doubt this trail is a challenge and for vintage machinery, I for one have never seen or heard of a classic bike complete this track in either direction. The difficulty is compounded by the scale of the ruts dug by modern dirt bikes and 4x4s, especially considering the TR5’s rigid foot pegs and very modest six-inch ground clearance.

Without doubt this trail is a challenge and for vintage machinery, I for one have never seen or heard of a classic bike complete this track in either direction. The difficulty is compounded by the scale of the ruts dug by modern dirt bikes and 4x4s, especially considering the TR5’s rigid foot pegs and very modest six-inch ground clearance.

RIDING A RIGID FRAME OFF ROAD

The ride began from Hikuai in misty but clearing weather promising a warm autumn day. The first part is easy enough following gravel roads and fairly level tracks with a few fords before crossing the modern highway and turning into the bush to begin with some trepidation the climb towards the summit. Now we were up against a rocky, rutted track that climbed steadily. Though the ride from the rigid frame is jolting by the standards of a modern machine with a foot of suspension travel, the TR5 was making great progress.

With only four gears on the steeper pitches first gear was required, but the TR5 revs as freely as it will chug down to idle, so quite a large speed range is possible in each gear. Though first gear is not as low as a modern bike the engine does a great job at low revs and the massive flywheel effect ensures that stalling is unlikely. Even with the rrigid rear end we soon We found the confidence to change up into second gear and take the rocks with more speed if the grades eased up.

However, we knew that further up the trail deteriorated badly and ahead of us was a couple of miles of really hard going where deep muddy 4x4 ruts were interposed with slippery rock slab climbs.

With only four gears on the steeper pitches first gear was required, but the TR5 revs as freely as it will chug down to idle, so quite a large speed range is possible in each gear. Though first gear is not as low as a modern bike the engine does a great job at low revs and the massive flywheel effect ensures that stalling is unlikely. Even with the rrigid rear end we soon We found the confidence to change up into second gear and take the rocks with more speed if the grades eased up.

However, we knew that further up the trail deteriorated badly and ahead of us was a couple of miles of really hard going where deep muddy 4x4 ruts were interposed with slippery rock slab climbs.

See the following page for helmet cam video of the ride across the Coromandel Ranges.

THEN IT GOT TOUGH

With much doubt we pulled up at the first truly daunting obstacle, a deep muddy uphill slot criss-crossed with ruts and mined with football-sized rocks. There was no chance of skirting this trap as it lay between three metre high forest clad banks. “Sure you want to do this to the old girl?” Dene called from the saddle of the quietly idling TR5. “It could be ugly. “Lets give it a go I said, just give it a bit of power, but don’t slip the clutch, it won’t take a flogging like a modern bike, and watch the rigid pegs on the rocks and don’t………….” But Dene had heard enough of my caution and was already gunning the old warrior into action in a positive attempt to storm the possibly impossible.

With the characteristic deep throated rasp of the two into one exhaust the TR5 went into its work cutting a swathe through the sticky mud and forging up the slot with minimal wheel spin and barely any loss of momentum, even though the pegs were cutting through the clay like leveling bars. On and up it went bumping over hidden rocks, up around the bend and out of sight. Silence.

Now it was my turn on the T100, no time for blousing the climb on this ‘modern' 46 year old bike. Just like the TR5, the T100 nailed the climb, even more easily thanks to plenty more ground clearance and the folding foot pegs.

Pulling up alongside Dene it was the moment to exchange (appropriate-for-the-time) back slaps and a more than a few cheers. Now we had a sense that this challenge was possible on vintage bikes and that far from being ancient boat anchors in the conditions, the old Triumphs were more capable than we had imagined and that we were being taught a lesson about their true potential.

With the characteristic deep throated rasp of the two into one exhaust the TR5 went into its work cutting a swathe through the sticky mud and forging up the slot with minimal wheel spin and barely any loss of momentum, even though the pegs were cutting through the clay like leveling bars. On and up it went bumping over hidden rocks, up around the bend and out of sight. Silence.

Now it was my turn on the T100, no time for blousing the climb on this ‘modern' 46 year old bike. Just like the TR5, the T100 nailed the climb, even more easily thanks to plenty more ground clearance and the folding foot pegs.

Pulling up alongside Dene it was the moment to exchange (appropriate-for-the-time) back slaps and a more than a few cheers. Now we had a sense that this challenge was possible on vintage bikes and that far from being ancient boat anchors in the conditions, the old Triumphs were more capable than we had imagined and that we were being taught a lesson about their true potential.

And so it proved. Despite the ruts, seat deep in places, the Triumph twins demonstrated their ancient arsenal of qualities, free revving engines with strong low down torque, and massive flywheels that promote an almost embarrassing amount of wheel grip.

The TR5’s low ground clearance and rigid pegs are a liability anywhere near ruts dug by modern bikes, but to a certain extent that deficiency is made up for with astounding traction and an almost subterranean centre of gravity. Though weighing somewhere just over 300 pounds and far more than a modern enduro bike the TR5 feels lighter and easier to manage in many respects than a taller modern adventure bike. Not a bad effort for what was in fact a fairly lightly modified road bike of the time.

The TR5’s low ground clearance and rigid pegs are a liability anywhere near ruts dug by modern bikes, but to a certain extent that deficiency is made up for with astounding traction and an almost subterranean centre of gravity. Though weighing somewhere just over 300 pounds and far more than a modern enduro bike the TR5 feels lighter and easier to manage in many respects than a taller modern adventure bike. Not a bad effort for what was in fact a fairly lightly modified road bike of the time.

FOUR SPEED REALITY CHECK

Having just four gears is a reality check. As first gear is low enough to storm ruts without getting heavily into the clutch and top is good for sixty miles and hour, the remaining two gears feel light years apart. The TR5 is not short of power, so it will pull the intermediate gears off road with little complaint, but each step is like shifting three gears on a modern bike, so there’s no such thing as changing up to go a little faster. On the Triumph you have to sure that you want to go a lot faster when you do change gear, because that's what's going to happen. After the ride we both wondered how much better these bikes would have been with five speed closer ratio gearboxes.

Riding a rigid bike off road takes some rapid adjustment. Though the telescopic forks work reasonably well the sensation of having no rear travel is dramatic to riders used to modern machinery. Having the front suspension work through it's travel, but without any rear movement at all creates a sensation of the bike changing attitude entirely around the rear axle. On smooth or rolling ground it’s no big drama, but on anything remotely bumpy the ride can be choppy to say the least. We found it was critical to modulate our speed to the terrain and be constantly ready to take the weight on the foot pegs. Over bumps with a wider spacing it seemed you could judge the speed to ensure the rear wheel contacted only with the tops of the bumps, in which case progress was relatively fast and smooth. However when the bumps are close-spaced it was harder to find the sweet spot. No doubt riders born to rigid bikes had the strategies to cope better than we did, they must have because I don't think my back would have survived a much longer ride and the thought of six days of such pounding is mind boggling. One thing we quickly learned was to watch out for big square edged bumps that can send the rear end skywards with a brutal and spine compressing and teeth clattering jolt.

Riding a rigid bike off road takes some rapid adjustment. Though the telescopic forks work reasonably well the sensation of having no rear travel is dramatic to riders used to modern machinery. Having the front suspension work through it's travel, but without any rear movement at all creates a sensation of the bike changing attitude entirely around the rear axle. On smooth or rolling ground it’s no big drama, but on anything remotely bumpy the ride can be choppy to say the least. We found it was critical to modulate our speed to the terrain and be constantly ready to take the weight on the foot pegs. Over bumps with a wider spacing it seemed you could judge the speed to ensure the rear wheel contacted only with the tops of the bumps, in which case progress was relatively fast and smooth. However when the bumps are close-spaced it was harder to find the sweet spot. No doubt riders born to rigid bikes had the strategies to cope better than we did, they must have because I don't think my back would have survived a much longer ride and the thought of six days of such pounding is mind boggling. One thing we quickly learned was to watch out for big square edged bumps that can send the rear end skywards with a brutal and spine compressing and teeth clattering jolt.

Having ridden the TR5 makes me all the more amazed at how riders like Jim Alves and his fellow team members stuck to these bikes, for days on end over rough terrain in the ISDT, not merely pottering along like we were but racing hard out to win successions of Gold Medals.

Now I'm more than ever certain that to do so they had backs of iron and balls of steel.

Now I'm more than ever certain that to do so they had backs of iron and balls of steel.

Almost all too soon it seemed the worst was over, and the Triumphs continued to cover the ground efficiently as the trail improved. We almost flew across the top of the range. The British vertical twin not only makes great roll on power, but the sound of the two into one exhaust must be the most satisfying there is. As the rough clay track turned to gravel road and then to seal we relished the unique sound and feel of these off road dinosaurs.

Returning to Hikuai over the modern tar sealed road was no let down. The TR5 is as good on road as off with just enough road speed to keep up with modern traffic - on twistier roads at least. We swung into the SH25’s copious bends for a glorious top gear ride back over the ranges with a feeling that the old Triumphs had acquitted themselves brilliantly and that we had both learned a fresh appreciation of our motorcycling heritage.